London Urology Clinic

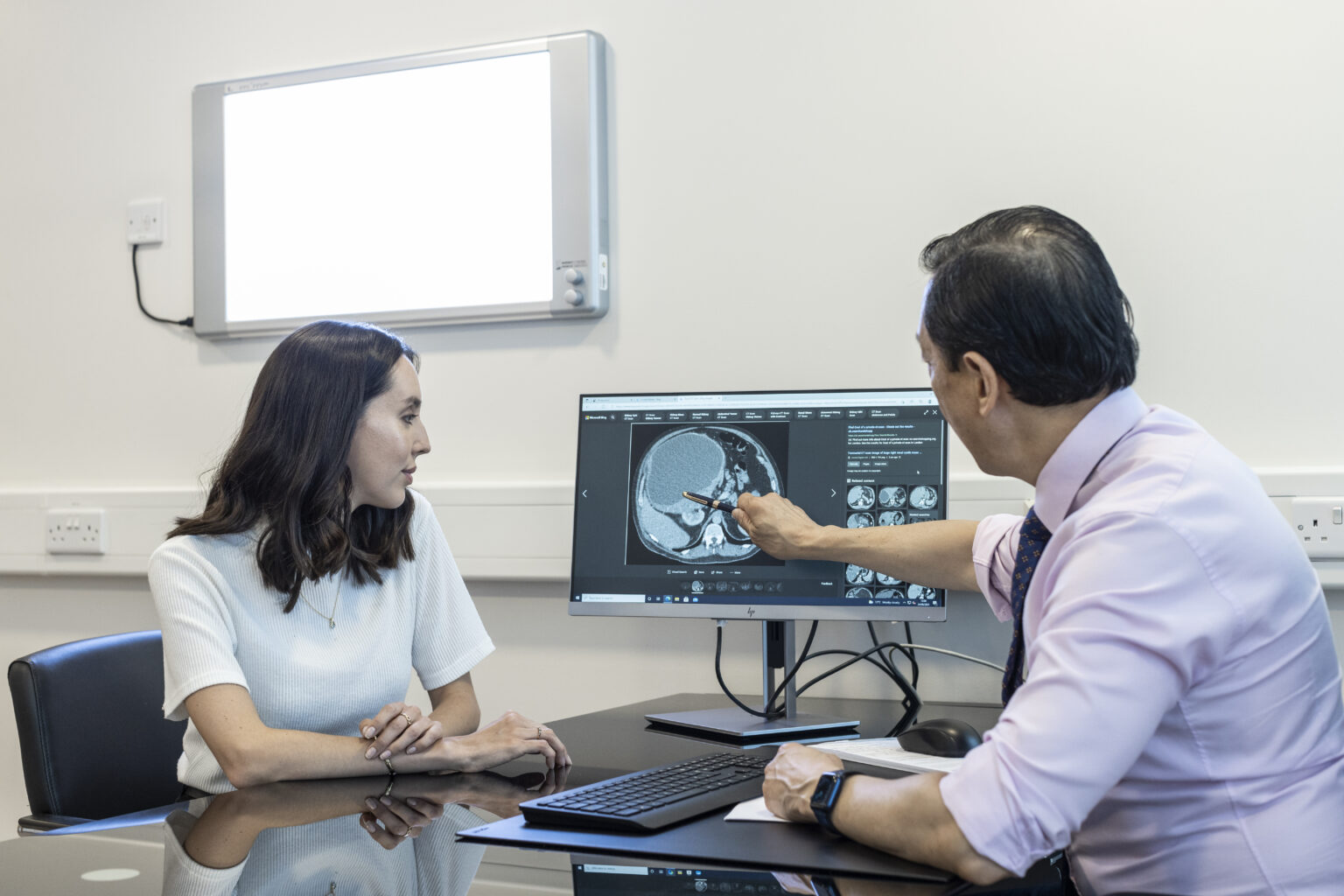

Our private urology clinic in London uses the latest techniques to give you the best diagnosis, intervention and aftercare for any urology problem you may be suffering from, allowing you to get back to your normal life as soon as possible.

We provide our urology consultants with the most modern diagnostic equipment, so they can quickly find out what’s wrong. They also have four operating theatres at their disposal to carry out procedures, which cuts waiting times.

You will enjoy the unique, family atmosphere of our hospital and its luxurious surroundings, making your stay as pleasant as possible.